Heat Pumps How Do They Work

Heat pumps have emerged as a leading technology for both heating and cooling in residential and commercial buildings. Unlike traditional furnaces that generate heat by burning fuel, heat pumps transfer heat from one place to another. This makes them incredibly energy-efficient, particularly in moderate climates. Understanding how heat pumps work is crucial for homeowners, HVAC technicians, and facility managers alike when making informed decisions about HVAC systems.

The Basic Principle: Heat Transfer

At its core, a heat pump operates on the principles of thermodynamics, specifically heat transfer. Heat naturally flows from warmer areas to cooler areas. A heat pump uses a refrigerant to facilitate this process, even when it seems counterintuitive, such as extracting heat from the cold outdoor air in winter.

The Components of a Heat Pump

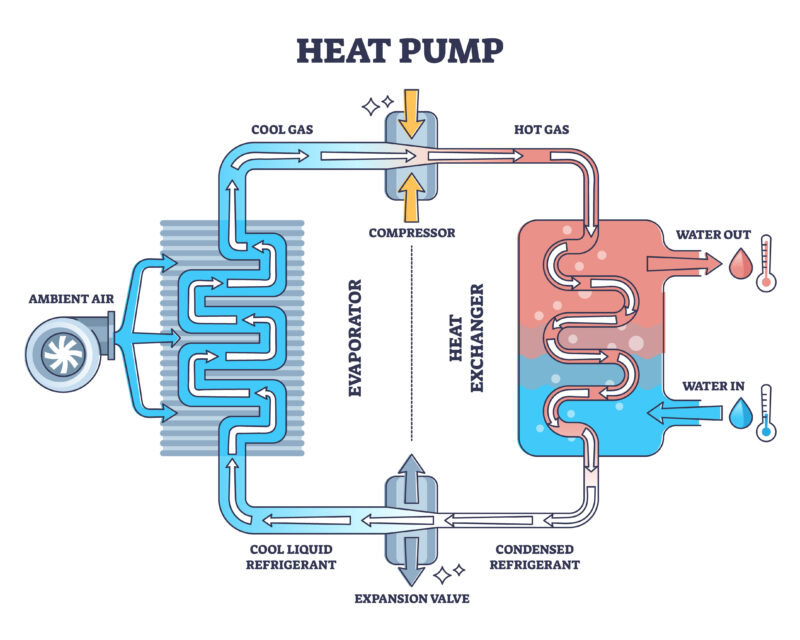

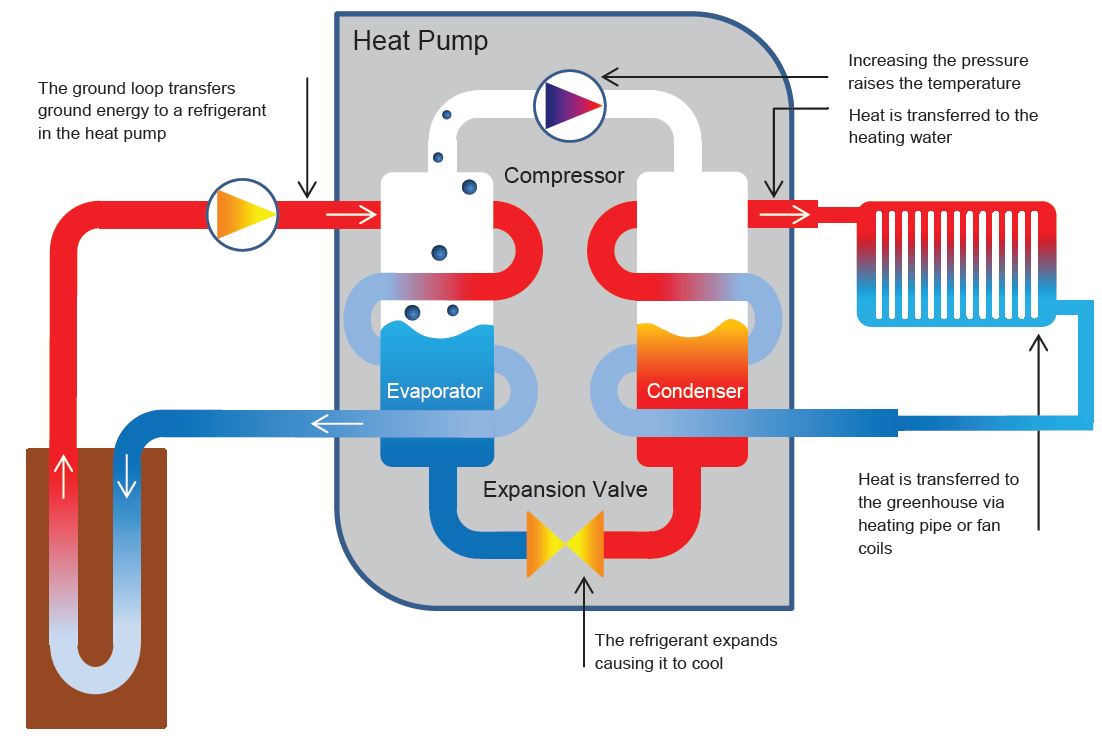

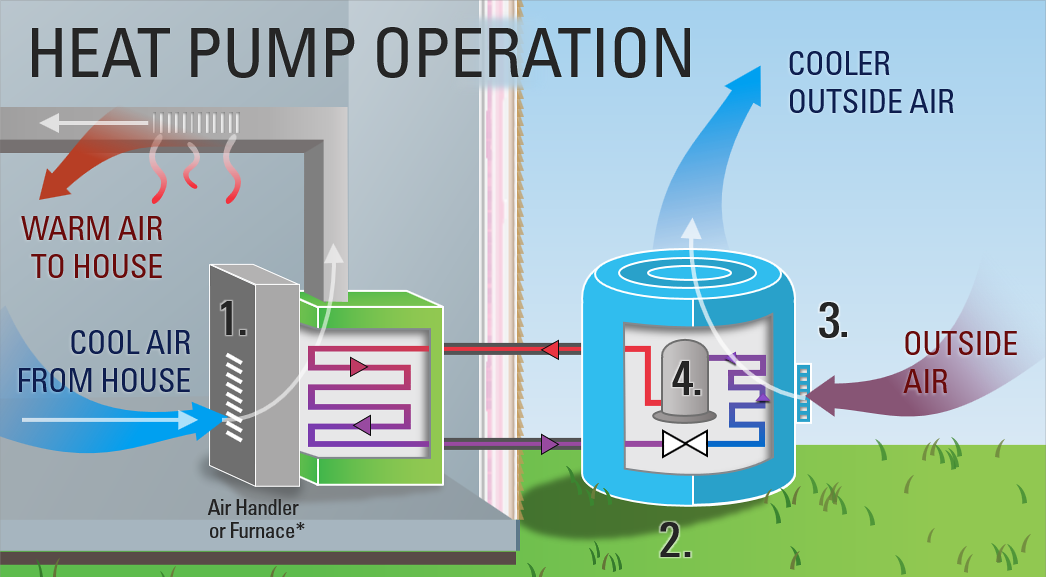

A typical heat pump system consists of two main components: an outdoor unit and an indoor unit. These units are connected by refrigerant lines that circulate the refrigerant. Key components include:

- Refrigerant: The working fluid that absorbs and releases heat as it changes state (liquid to gas and vice versa). Common refrigerants include R-410A and the newer, more environmentally friendly R-32.

- Compressor: The heart of the heat pump, which pressurizes the refrigerant, raising its temperature. Located in the outdoor unit.

- Condenser Coils: A heat exchanger where the hot, high-pressure refrigerant releases heat, condensing back into a liquid. It serves as either the indoor or outdoor coil, depending on the operating mode (heating or cooling).

- Evaporator Coils: A heat exchanger where the liquid refrigerant absorbs heat and evaporates into a gas. It serves as either the indoor or outdoor coil, depending on the operating mode.

- Expansion Valve (or Metering Device): Controls the flow of refrigerant into the evaporator, reducing its pressure and temperature.

- Reversing Valve: A critical component that allows the heat pump to switch between heating and cooling modes by reversing the flow of refrigerant.

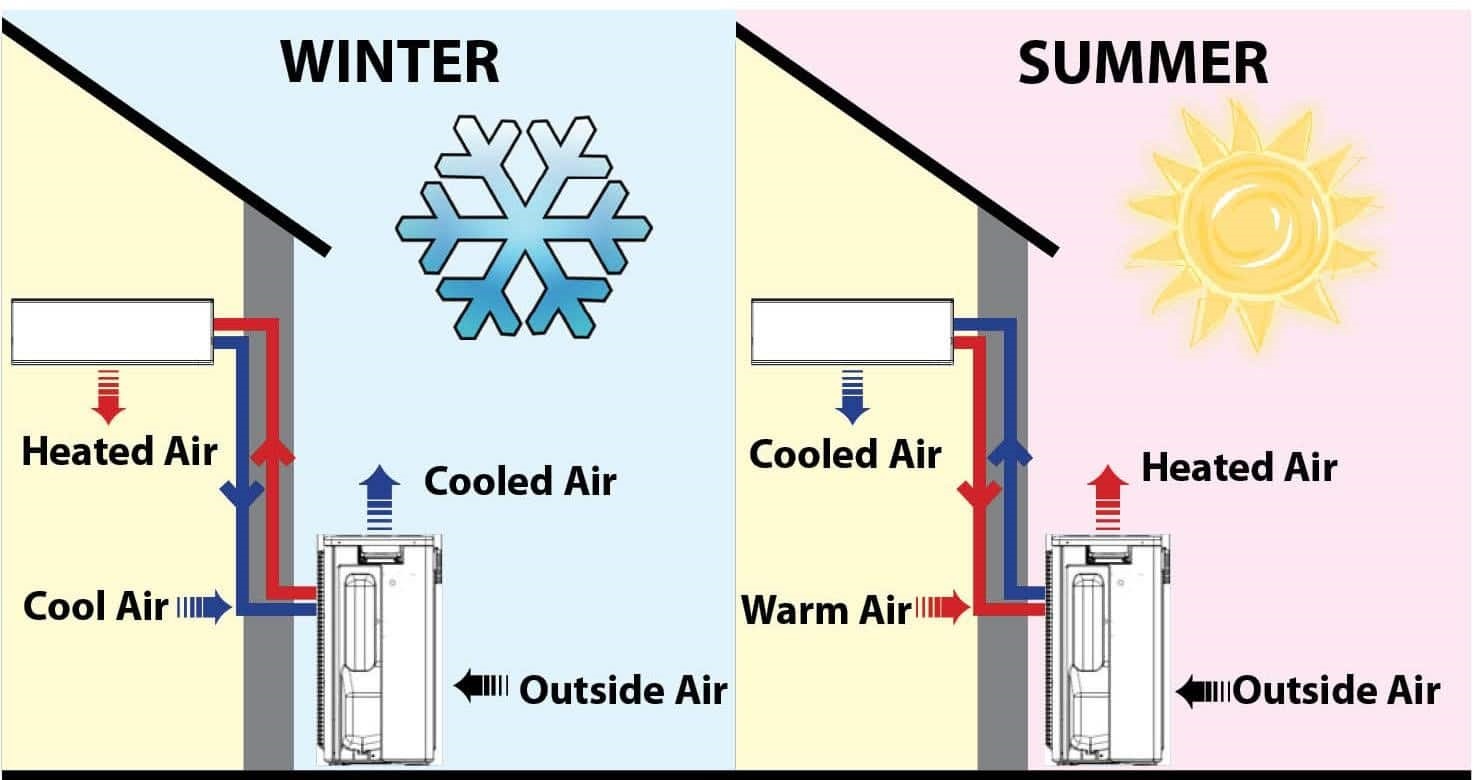

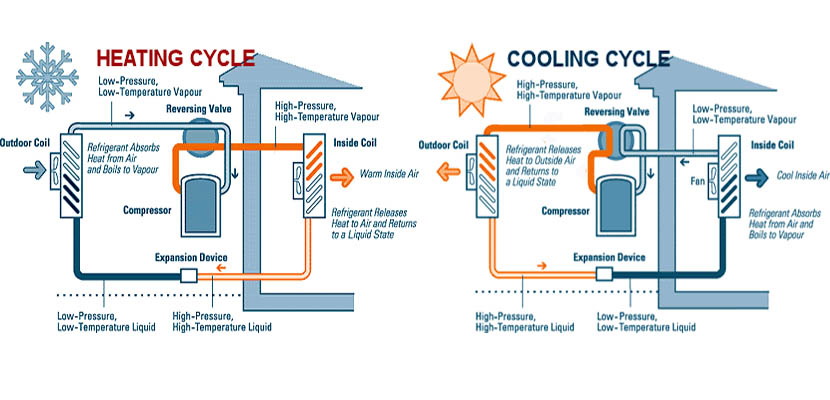

The Heating Cycle

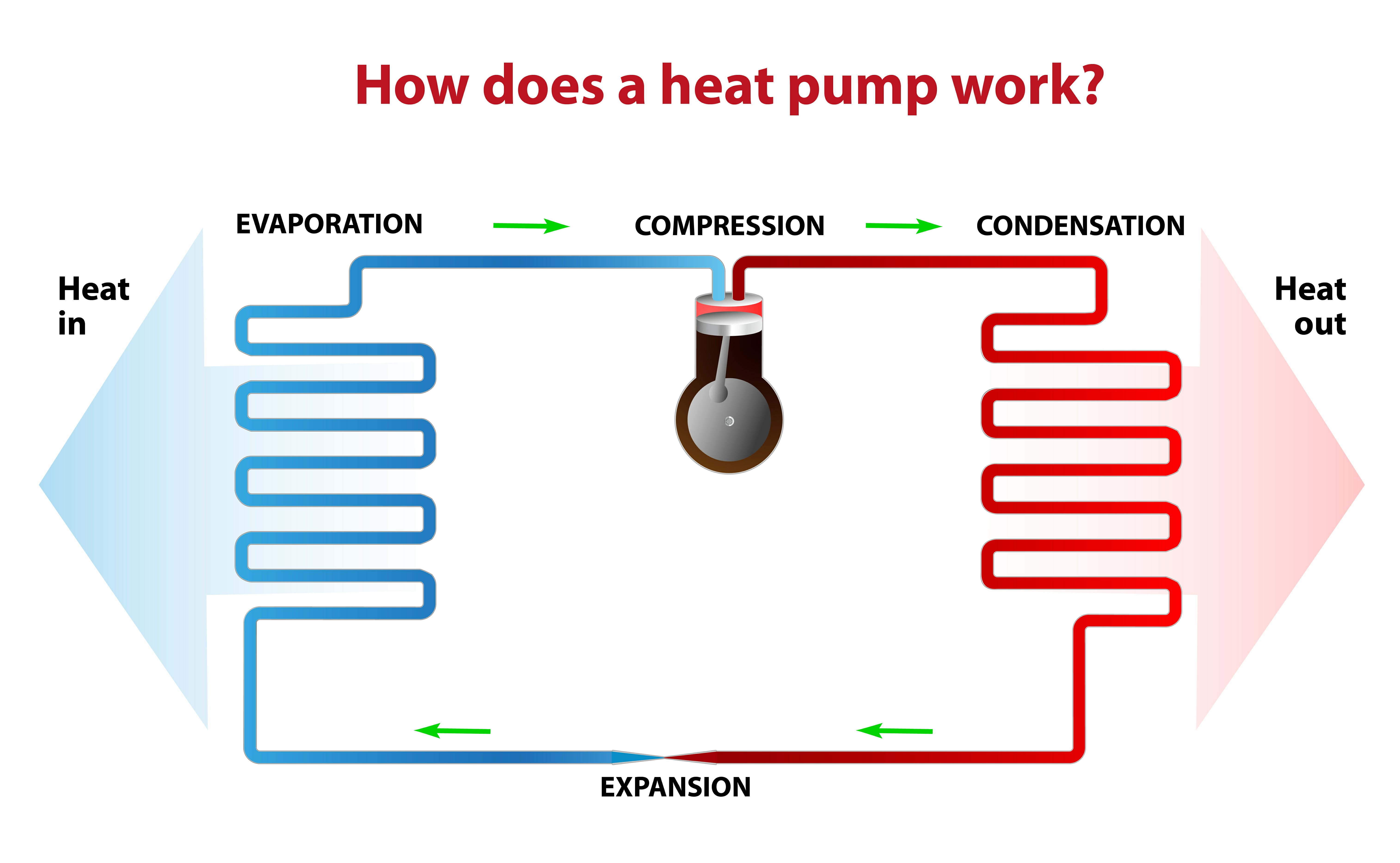

During the heating cycle, the heat pump extracts heat from the outdoor air and transfers it inside. Here's a step-by-step explanation:

- Evaporation: The cold, low-pressure liquid refrigerant flows through the outdoor evaporator coil. Even on a cold day, the outdoor air contains some heat energy. The refrigerant absorbs this heat, causing it to evaporate into a low-pressure gas.

- Compression: The low-pressure gas refrigerant is drawn into the compressor. The compressor increases the pressure and temperature of the refrigerant.

- Condensation: The hot, high-pressure gas refrigerant flows into the indoor condenser coil. Here, it releases its heat to the indoor air, warming the building. As it releases heat, the refrigerant condenses back into a high-pressure liquid.

- Expansion: The high-pressure liquid refrigerant flows through the expansion valve, which reduces its pressure and temperature. The now cold, low-pressure liquid refrigerant returns to the outdoor evaporator coil to repeat the cycle.

It's important to note that heat pumps can extract heat from surprisingly cold air. Modern heat pumps can operate efficiently even when outdoor temperatures are near freezing. Some advanced models, known as cold-climate heat pumps, are designed to operate effectively in even colder temperatures, sometimes down to -13°F (-25°C) or lower. These models often incorporate features like larger coils, more advanced compressors, and base pan heaters to prevent ice buildup.

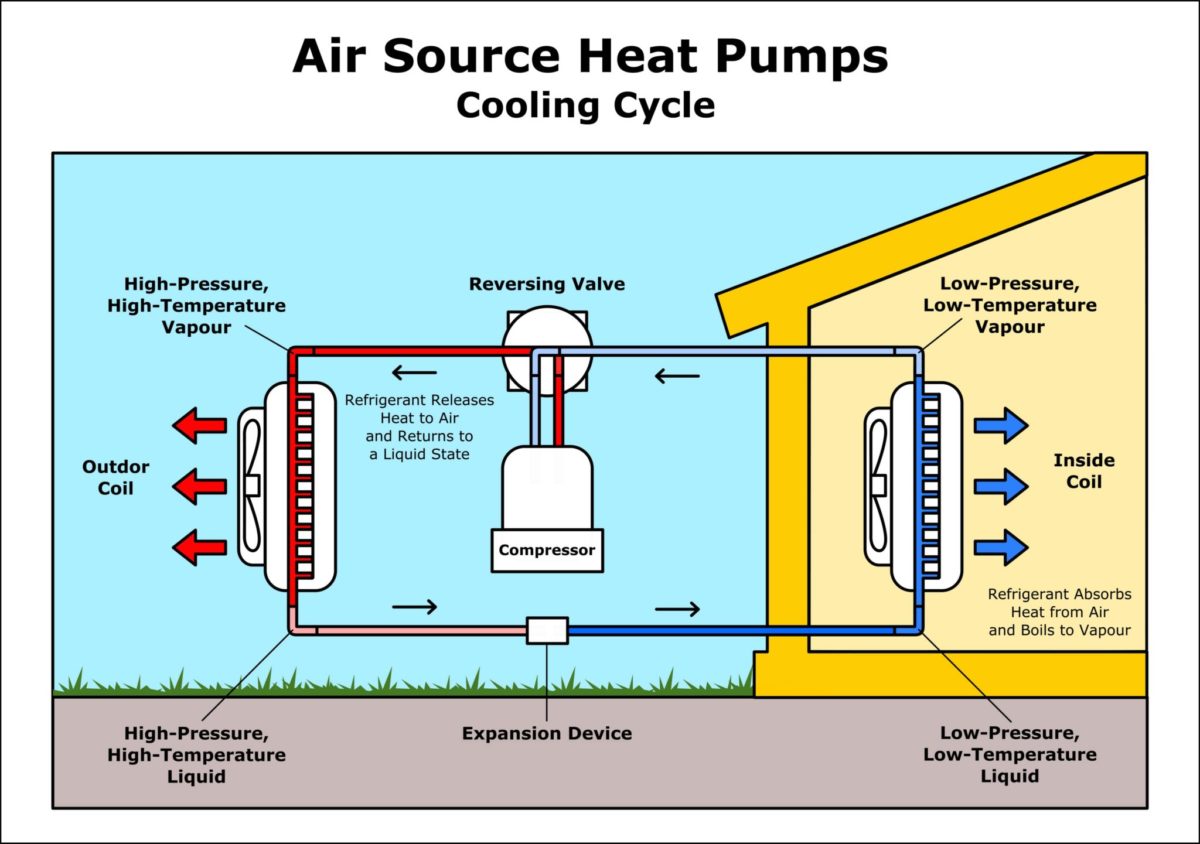

The Cooling Cycle

In the cooling cycle, the heat pump reverses its operation to extract heat from the indoor air and transfer it outside, functioning essentially like an air conditioner.

- Evaporation: The cold, low-pressure liquid refrigerant flows through the indoor evaporator coil. The refrigerant absorbs heat from the indoor air, cooling the building. As it absorbs heat, the refrigerant evaporates into a low-pressure gas.

- Compression: The low-pressure gas refrigerant is drawn into the compressor, which increases its pressure and temperature.

- Condensation: The hot, high-pressure gas refrigerant flows into the outdoor condenser coil. Here, it releases its heat to the outdoor air, cooling and condensing back into a high-pressure liquid.

- Expansion: The high-pressure liquid refrigerant flows through the expansion valve, reducing its pressure and temperature. The now cold, low-pressure liquid refrigerant returns to the indoor evaporator coil to repeat the cycle.

The reversing valve is key to switching between heating and cooling modes. By changing the direction of refrigerant flow, the heat pump effectively swaps the roles of the indoor and outdoor coils.

Types of Heat Pumps

There are several types of heat pumps, each with its own advantages and disadvantages:

- Air-Source Heat Pumps (ASHP): The most common type, ASHPs transfer heat between the indoor air and the outdoor air. They are relatively inexpensive to install but can be less efficient in extremely cold weather.

- Geothermal Heat Pumps (GSHP): Also known as ground-source heat pumps, GSHPs transfer heat between the indoor air and the ground or a nearby body of water. The ground temperature remains relatively constant year-round, making GSHPs more efficient than ASHPs, especially in extreme climates. However, they have a higher upfront installation cost due to the need for underground piping.

- Water-Source Heat Pumps (WSHP): Similar to GSHPs, WSHPs use a body of water (lake, river, or well) as a heat source or sink. They are often used in commercial buildings with readily available water sources.

- Ductless Mini-Split Heat Pumps: These systems consist of an outdoor unit and one or more indoor units, connected by refrigerant lines. They do not require ductwork, making them ideal for homes without existing duct systems or for adding heating and cooling to individual rooms.

Efficiency Ratings: SEER, HSPF, and COP

The efficiency of a heat pump is measured by several ratings:

- Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio (SEER): Measures the cooling efficiency of a heat pump. A higher SEER rating indicates better energy efficiency. Current minimum SEER requirement is 14 or 15, depending on location.

- Heating Seasonal Performance Factor (HSPF): Measures the heating efficiency of a heat pump. A higher HSPF rating indicates better energy efficiency. The current minimum HSPF requirement is 8.8.

- Coefficient of Performance (COP): Measures the ratio of heating or cooling output to energy input at a specific operating point. Higher COP indicates better efficiency. While SEER and HSPF are more commonly used for residential systems, COP is often used for commercial applications and specific performance testing.

When comparing heat pumps, it's essential to consider all three ratings to get a complete picture of their energy efficiency in both heating and cooling modes.

Cost and Lifespan

The initial cost of a heat pump can vary depending on the type, size, and complexity of the installation. ASHPs are generally less expensive to install than GSHPs. However, GSHPs often have lower operating costs due to their higher efficiency.

The lifespan of a heat pump typically ranges from 15 to 20 years with proper maintenance. Regular maintenance, such as cleaning coils, replacing air filters, and inspecting refrigerant levels, can help extend the life of the system and maintain its efficiency. The lifespan can be affected by factors such as climate, usage patterns, and quality of installation.

Maintenance Tips for Homeowners and Facility Managers

Regular maintenance is crucial for maximizing the efficiency and lifespan of a heat pump system. Here are some essential maintenance tips:

- Change Air Filters Regularly: Dirty air filters restrict airflow, reducing efficiency and potentially damaging the system. Replace filters every 1-3 months, depending on usage and air quality.

- Clean Outdoor Coils: Keep the outdoor coils free of debris, such as leaves, dirt, and snow. Use a garden hose to gently clean the coils.

- Schedule Professional Maintenance: Have a qualified HVAC technician inspect the system annually to check refrigerant levels, electrical connections, and other components.

- Monitor Performance: Pay attention to any unusual noises, smells, or performance issues. Address problems promptly to prevent further damage.

- Consider a Service Agreement: Many HVAC companies offer service agreements that include regular maintenance and discounts on repairs.

Real-World Performance Examples

Consider a homeowner in a moderate climate (e.g., the Mid-Atlantic region) comparing a traditional gas furnace with an ASHP. The gas furnace might have an efficiency of 80-90%, while the ASHP might have an HSPF of 9 or higher. In this scenario, the ASHP could potentially provide significant energy savings, especially during milder winters. However, on extremely cold days, the heat pump's efficiency may decrease, and supplemental heating (e.g., electric resistance heat) may be required.

In contrast, a commercial building using a GSHP system in a northern climate might see even greater savings due to the consistent ground temperature. While the initial investment is higher, the lower operating costs and longer lifespan of the GSHP can result in a significant return on investment over time.

Conclusion

Heat pumps offer an energy-efficient and versatile solution for both heating and cooling. By understanding the basic principles of heat transfer, the different types of heat pumps, and the importance of proper maintenance, homeowners, HVAC technicians, and facility managers can make informed decisions about selecting, installing, and maintaining these systems. While the initial cost can be a factor, the long-term energy savings and environmental benefits of heat pumps make them a compelling choice for sustainable HVAC solutions. Keeping abreast of technological advancements, such as new refrigerants and improved compressor designs, is crucial for optimizing the performance and efficiency of heat pump systems.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1225021365-8424e0bfe36b4254862d3f0ca5031a94.jpg)